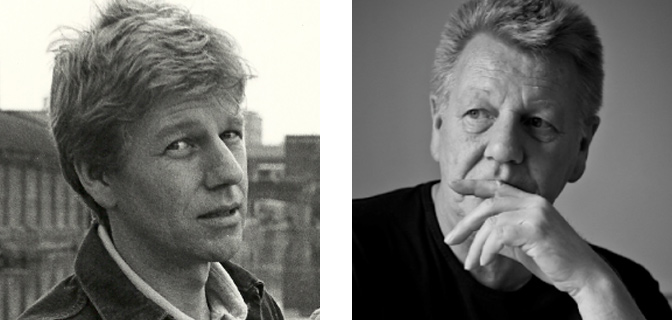

RON PECK

A KIND OF BIOGRAPHY

Well…

Photos of Ron Peck: (Left) photographer unknown; (Right) photographer Grégory Maillot.

1

2nd November 2016

I prefer to present content as a jigsaw...

— RON PECK

What do I say about myself? In a way I prefer the films themselves to say it all for me. Each project, made or unmade, was a consuming process and an adventure that defined and expressed a different part of my life.

I could provide a strict chronology of the projects I worked on but I prefer to go back to the jigsaw idea mentioned in the Introduction to this site, starting not at the beginning but somewhere in the middle, with three of the East London films and with Team Pictures.

So, apart from saying that I was born in 1948, in Merton Park, South London, I’m mostly going to skip for the moment schools, colleges and the first films and dive in at 1990, which is when I shot Fighters.

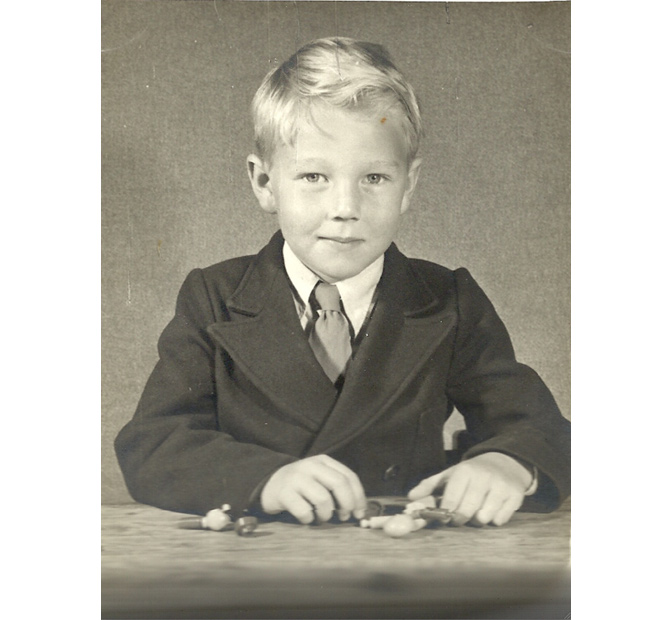

But I will provide a photo from an earlier time, a clue.

A great playground for a child.

The family garden in Merton Park where I spent my childhood and lived a very different life to the Bethnal Green life I have lived, off-an-on, since 1975.

I could add one more photo, the kind we all had taken at primary school when we were young.

I guess I must be about 5 or 6 there, looking smarter than I ever remember being at that age. I note a certain direct look at the camera encouraged by the school photographer no doubt, I’d even say a certain defiance and determination, when in fact I was really very shy and unsure of myself. But 5 years later I did know I wanted to work in films.

Moving to Bethnal Green in East London, when I was 27, was a jump. It felt like another city, not the London I knew at all. By 1990, when Fighters was being worked on, I was by then, some said, already an adopted East Ender. I certainly felt at home here, but I think I only really began to understand East London in a different and deeper sense through the making of Fighters, which I worked on with Mark Ayres and made through our joint company, Team Pictures.

The genesis of that film can be found in the entry on Fighters. I should say it wasn’t the first film I had made or been involved in about East London. There were all those very important earlier years at Four Corners, to be written about here later, and it was only because of those years that I knew East London at all.

One significant East London film made before Fighters – and the one that led directly to it – was a film called Empire State, which dramatized the fight over a piece of land on which an East End nightclub stood and held its ground, caught up in the much bigger struggle over the wholesale regeneration of Docklands.

It aspired to be epic but, in the end, was more a kind of melodrama, though still on quite a scale. Very significantly, one of the characters in it was a boxer, and played by a real ex-professional boxer, Jimmy Flint. That started my interest in boxing in a serious way.

Fighters was an attempt to go right to the heart of the matter, deep into boxing, all the way, out of the studio and back into the streets again and into the hard-core boxing gyms. There is a scene in a boxing gym in Empire State, filmed in South London, but the action in it was a reconstruction, pure fiction to further the drama. Fighters took me to the real thing, which was much more exciting and dramatic, and I spent many months at West Ham Boys Club, the Royal Oak and later the Peacock Gym in Canning Town taking it all in and felt at last I was beginning to understand the sport, thanks to the boxers I got to know and to trainer Jimmy Tibbs.

Canning Town then couldn’t have been further from where I grew up in Merton Park, though my last visit to that part of South London several years ago showed a district in steep decline and suffering neglect. It was no longer the district of green, well-kept gardens, parks and commons that I grew up in and played safely in as a kid. The trees still blossomed and the daffodils still came up but no one looked after these things any more. Nature just took its own course.

Canning Town was surely never green in that suburban sense. It felt tough as nails. Dangerous like those East Side districts in the Cagney and Bogart crime films. It was the hard men (and women) I met through Fighters (and later Real Money) who looked after me and showed me round, shared their lives with me, their family lives as well as their gym lives. And from this boxing community came some of my closest friends.

The experience of making Fighters led to making another film for Channel 4, Real Money, with the same people, this time an acted drama about the criminal code. That film, like Fighters, went down incredibly well with audiences and critics and we tried soon after (but sadly failed) to make a larger cinema film, Gangster, a dynastic family drama, with the same actors. It might have ended up being the best film of them all, but we were stopped in our all-too-enthusiastic tracks. That’s another whole story to be told later on this site.

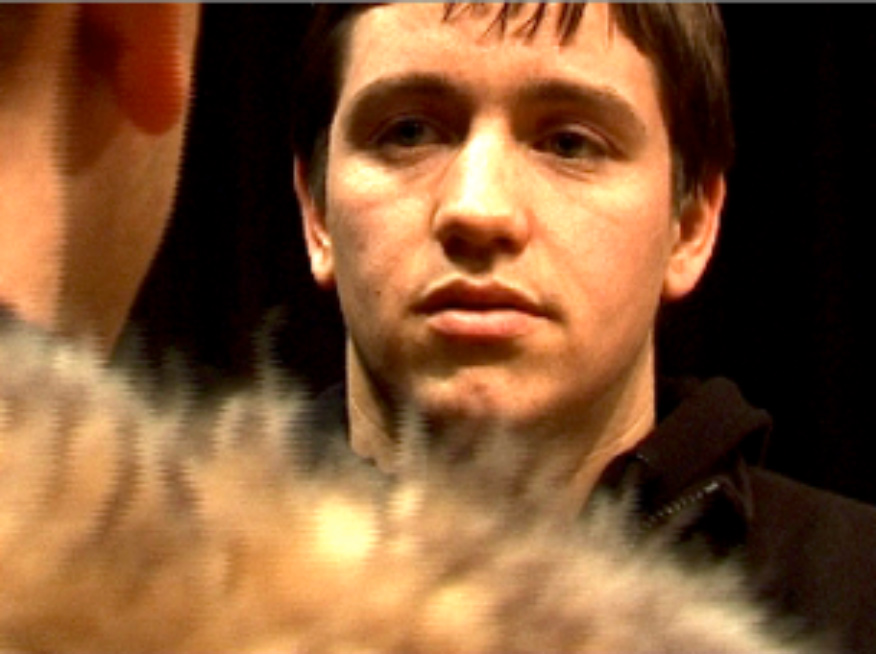

Mickey May fills Jimmy Tibbs in on how things have changed while he’s been away in prison in a workshop for Gangster.

With Gangster, we got as far as writing a script and developing ideas in the acting workshop at the studio (see the compilation on the Real Money DVD) and we tried everywhere we could to set it up as a production, but for a £2 million budget financiers wanted stars and tightly written scripts. Michael Caine was mentioned. Bob Hoskins. Understandable perhaps. But we wanted to create our own stars from the non-professionals we were working with in Canning Town, using their own street experience and edgy improvised dialogue rather than clichéd cinema gangster slang. They had genuine screen presence and knowledge. To Mark and I that was crystal clear and very exciting. I honestly thought we had found our own Cagney, De Niro and James Dean in Canning Town and it was that belief that kept me pushing.

It has always been a rule of thumb with me that, given how many of the projects you work on and develop don’t actually get made, the experience of the effort to make them and the actual projects themselves have to be ambitious, engaging and worthwhile. That way you get something out of it, made or not, and don’t simply waste your life on your knees in front of producers and financiers. I had to see each project as a voyage, a striking out into new territory, an enlargement of my experience. Life after all is short. You want to live what you have of it.

At least 3 years was spent working on Gangster. The demands of staying with it took everything to the brink – both for myself and for Team Pictures – and another direction had to be taken if we were not just to go under. Applications were made to the Lottery Arts Fund and to the European Regional Development Fund, which were pouring money at the time into regeneration projects in East London and around the country. To my surprise the applications were successful.

In 1996 Team was refurbished and re-equipped, but at the same time had a several year programme of outputs to deliver – jobs, training, promotion of neglected minority groups, subsidised production facilities to help build up new ‘cultural industries’.

Overnight, Team became by default primarily a facilities company, renting out cameras and other filmmaking equipment. It took up all our time and energy to run this side of things. Efforts were made to keep Gangster going and to get other productions off the ground but I had little luck and not enough time. I was told the projects were too maverick and our own production programme at this time pretty much ground to a halt.

But at the tail end of this period, around 2008, I set up an acting workshop again. Mark Tibbs, who had been centrally involved in Fighters and Real Money, brought to the studio a young fighter he was training, Alan Milton, someone he thought might be good on-camera. We tried out some ideas based on sibling rivalry. It seemed to work. And the more we worked the better it got. I pulled what we learned from the workshops together and created a drama set mostly on a cross-Channel ferry, developing a tale about collecting some dodgy money from France. I called it Cross-Channel.

Alan Milton plays opposite Mark Tibbs in one of the workshops at Team Pictures that developed Cross-Channel.

Empire State built an ocean liner in a studio, and had a budget of almost £2,000,000, whereas Cross-Channel was shot mostly on an actual ship on the sea and cost £20,000. The bigger film was shot on 35mm film. The smaller film on DVCAM and mini-DV digital tape. One had a crew of about 100. The other a crew of 3 or 4 (and often just myself with my DVCAM camera). But I found the later film a bracing experience and felt I’d made something genuinely different. It suggested to me that interesting films in the future could be made much more on this basis.

The brothers in Cross-Channel had mobile phones that were already also cameras. It felt like this technology was releasing something that could be the breaking wave of a new and exciting way to make films… and now, of course, people are shooting whole features on their phones…

On the Cross-Channel ferry 2008 (photo by François Théault).